Isolation inspires local sculptor to create his artistic interpretations of COVID-19

by Jay Korff

Thursday, May 7th 2020

ARLINGTON, Va. (ABC7) — Hadrian Mendoza’s front deck in Arlington has been an oasis for this potter, sculptor and educator.

“You’re stuck. This is great therapy. My hands are always moving," says the 46-year-old Filipino-born artist.

His small outdoor spot has served for weeks as a stay-at-home safe space from a health crisis gnawing at the nation.

Mendoza says, “How can I not go crazy when you can’t leave your home? I have this.”

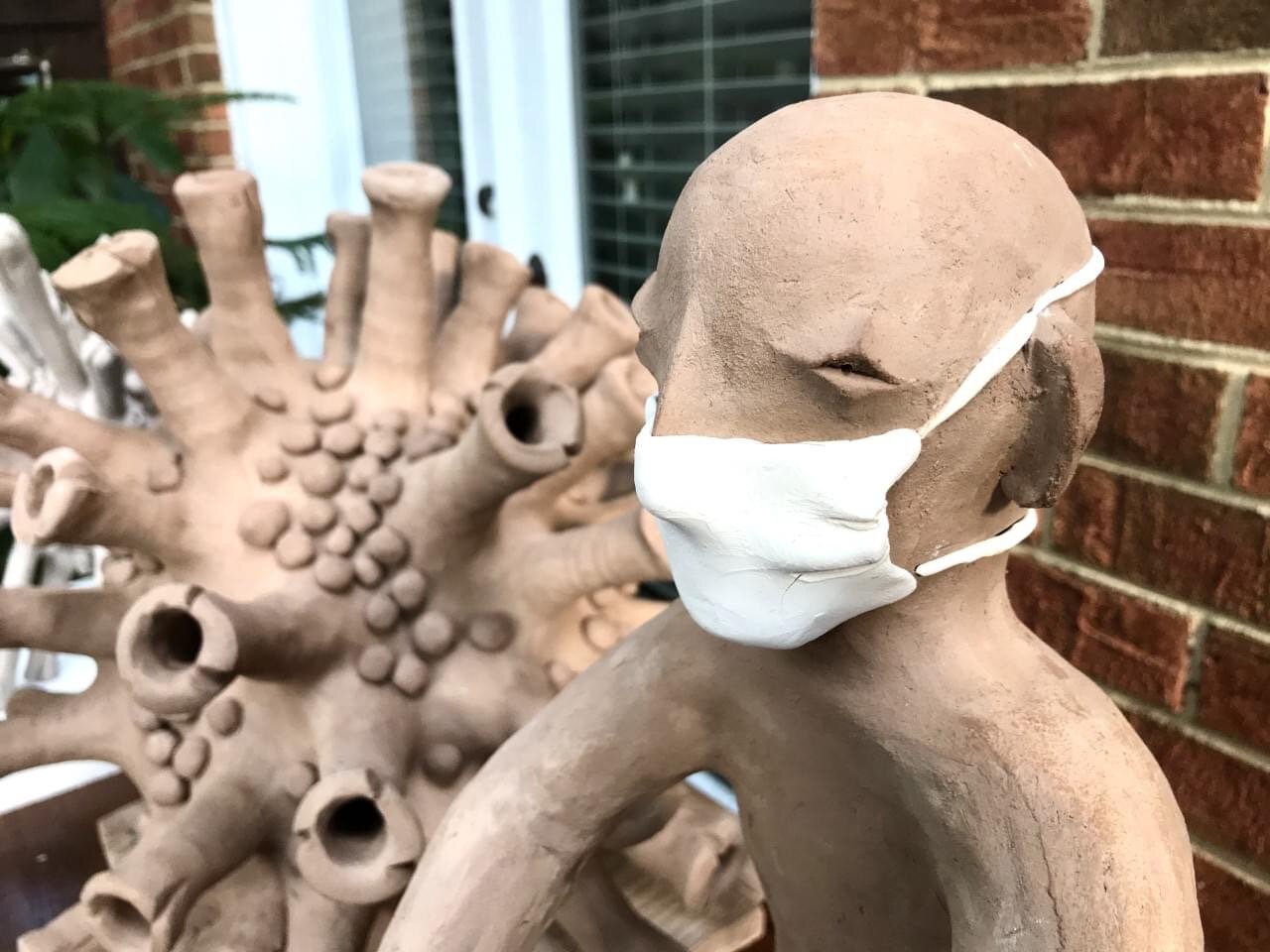

Mendoza’s isolation inspired him to create a series of eight evocative pieces. They are his artistic interpretations of the mask and the COVID-19 virus: the defining symbols of the pandemic.

“I saw a virus in a microscope and I thought it was pretty despite the fact that it’s dangerous,” says Mendoza.

And it's the powerful juxtaposition of danger and beauty that Mendoza is trying to capture.

“We are kind of like journalists. We reflect what’s going on today through our own eyes," adds Mendoza.

Despite restless weeks of worry, Mendoza’s focus here is on history and hope. The masked figure in his series is based on a mythological deity from The Philippines called Bulol: guardian of rice fields. Bulol's presence is meant to bring a plentiful harvest. In this case, a cure for COVID-19.

“Of course, every person does have a mask and you can’t tell who anyone is," says Mendoza.

Mendoza plans to fire and complete his pieces in the fall when this viral storm has hopefully cleared.

Mendoza adds, "I’m going to aim for a reddish-blue kind of like what the real virus looks like."

Half of his pieces in this series have already been spoken for even though they aren’t done.

“We’re all waiting and so are they," says Mendoza.

Mendoza, a graduate of the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, is also the Art Director at St. Thomas More Cathedral School in Arlington.

Visualizing a Virus: Alum’s Art Captures Emotions of a Pandemic

MAY 5, 2020 BY LAURA MOYER

University of Mary Washington Online News

Hadrian Mendoza isn’t glorifying the novel coronavirus at the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in images of the tiny particle, he sees more than fear, suffering, loss and grief.

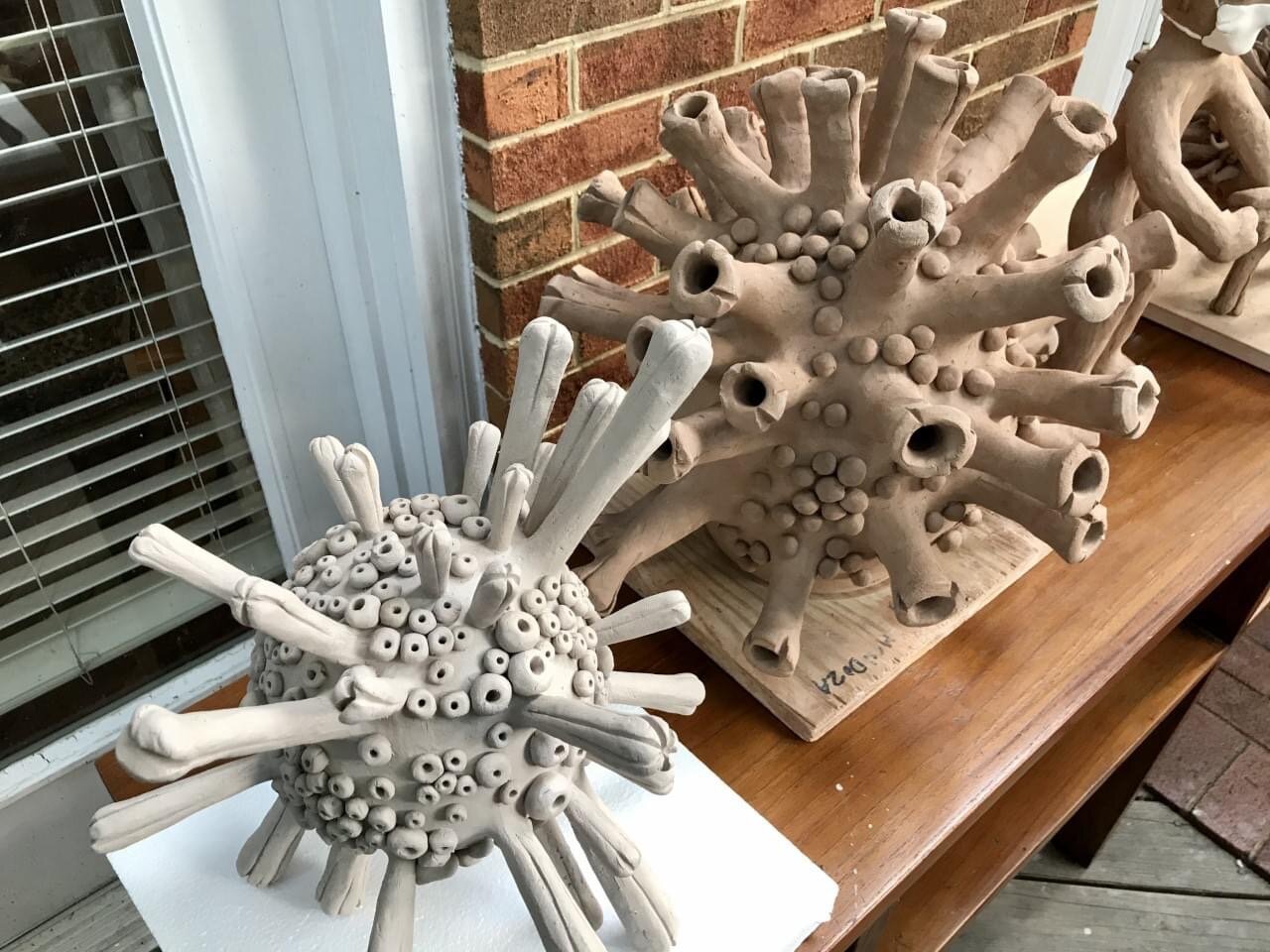

To Mendoza, a 1996 Mary Washington graduate and internationally known fine-arts potter, viruses have long represented a fascinating intersection of danger and beauty. Starting in 2016, he began creating sculptural interpretations of viruses – his creations then were hollow spheres with sharp, spiny protrusions that served both to balance and to convey threat.

In early March, when Mendoza’s family found themselves isolating in their Arlington, Virginia, townhouse, the idea “crept back into my mind,” he said. From his makeshift front-porch studio, he conceived a sculptural version of a coronavirus. It’s less a rendering of the actual virus than a reimagining that captures the many emotions engendered by the pandemic. The result is art at its most timely, a reflection of current events and of the universal attempt to contain and control what affects us.

A business administration major in his Mary Washington days, Mendoza takes seriously the financial aspects of his artistic profession. He already has three commissions for versions of the coronavirus, all from collectors in his native Philippines, where he has held two solo exhibitions a year for 12 years.

It is satisfying, he said of his current work, “to take something negative and bring something positive out of it.”

Where the 2016 virus sculptures captured a certain snowflake-like quality, unique but symmetrical, Mendoza’s coronavirus is intentionally random, with rounded protrusions of different sizes that elevate and support the center. Even so, he said, the form has a pleasing quality.

“I try to make it look as disgusting and nasty as I can, because that’s what it really is,” Mendoza said. “But when you try to make it look so gross, it ends up beautiful.”

The glazing that enhanced the danger and beauty of Mendoza’s earlier viruses has yet to be completed on the coronavirus works. Isolating at home leaves him no way to fire his pieces. When social-distancing restrictions lift, though, Mendoza plans to use a wood-burning kiln and an oxblood glaze for a color effect that is chiefly red with light blue tones.

Meanwhile, he is making the best of unforeseen circumstances.

Mendoza is the full-time art director for St. Thomas More School in Arlington, and he has adapted to teach his students via videoconference. He assigns projects to challenge their creativity using materials they have on hand.

His wife is working from home now, too, and their children, in eighth and fifth grades, are attending school remotely. “With four of us here, we’ve had a lot of bonding time,” he said. “It slows everything down.”

Mendoza has enjoyed a boost in studio time, even if the studio is outside and open-air. And he’s found creating the coronavirus pieces oddly therapeutic, a respite from being stuck in place and a welcome reminder of creating his earlier virus artworks.

“For me, I’m just creating,” he said. “I see it as picking up where I left off.”

Artist Hadrian Mendoza recreates his 'Virus' to reflect today's troubled times

The US-based stoneware potter created two separate pieces in 2016 that spoke of beauty mixed with danger. A couple of weeks ago, he revisits the concept to depict the COVID-19 crisis.

BY BARBARA MAE NAREDO DACANAY

ABS-CBN News, Philippines

ANCX | Apr 16 2020

In 2016, Hadrian Z. Mendoza presented sculptures to the world as symbols of danger, unaware of the COVID-19 menace that would envelope the globe a few years later. “I wasn’t prophetic,” the Virginia-based stoneware artist of his two earlier pieces called “Virus,” that were exhibited in separate shows in the Philippines and United States.

Earlier this month, he decided on creating an updated version of his piece. This time, he made use of a microscopic image of the deadly coronavirus as his inspiration.

Mendoza was initially inspired by a microscopic image of a virus he was unable to identify. Photo from www.hadrianmendozapottery.com

Both of Mendoza’s 2016 “Virus” pieces almost look alike; Both have 10-inch long cone-like protrusions with spiral indentions. making them look like long-stemmed seashells. Each cone was perilously shaped and carefully embedded into a 30-inch roundish base, resulting in an unusual ball-like artwork. One “Virus” has blue-brow tentacles and a blue-alabaster body. The other has chocolate-brown tentacles and a light brown body. The tip of their protrusions, with prickly menace, attracts the eyes and deeply grips the heart.

A tale of three viruses

The bluish “Virus” was shown at Ayala Museum’s Art Space from December 8 to 22, 2016. When Mendoza curated his show at Ayala, he placed his tentacled piece at the center of a group of six large and overpowering heads. “The heads and faces represented different cultures, just like the environment of multi-ethnicity in the US or Europe. I wanted to show people of the whole world with unanimous intent,” he explains.

All of the heads, however, look away from the smaller “Virus,” as if evading the unseen magnitude of its malady. Mendoza says that this orientation projects a cautionary visual narrative. “I didn’t want the faces to eyeball the Virus to show its menace and danger,” Mendoza explained, adding the blocking of the installation was needed because the “Virus” actually “looked beautiful and is compelling to watch.”

Instead of spikes, Mendoza's 2020 "Virus" has suckers, mimicking the "crowns" on top of COVID-19. Top right: Mendoza's wife Kim Nieves, a UP arts graduate now with the World Bank's International Finance Corporation, also made a Virus sculpture. Bottom left: Mendoza's Bulol is updated with a face mask to match our present reality.

Mendoza’s brownish “Virus,” on the other hand, was shown in an exhibit entitled “Homegrown Talent” at District Clay Gallery on Douglas Street, Northeast Washington D.C., from November 19 to December 31, 2016. “At District Clay, the curator placed ‘Virus’ in the center of the gallery. It was presented alone, on its own,” says Mendoza, adding the curator believed it was not necessary to tell a story around it or explain what the piece was all about.

The 2020 “Virus,” on the other hand, has a rounder base, and is studded with multi triangular tentacles that are less pointed. The spikes end with roundish knobs that look like suckers. Scientists call them clumps or S proteins that bite and bind cells. They are supposed to be red. But Mendoza’s stoneware “Virus” is brownish, as if petrified or made to look like an artifact.

Erlinda Halili, whose family owns Manila’s Aspac Airfreight International bought Mendoza’s blue piece while Cass Johnson, owner of DC’s District Clay purchased the brown version. Mendoza says the buyer of the recently made Covid-19 “Virus” wants to remain anonymous.

Mendoza's Ayala Museum "Virus" was shown at its section, Art Space, from December 8 to 22, 2016.

“I once saw beautiful images of a virus in a microscope. I could not remember its name. But I remember asking why a dangerous and invisible virus could look so beautiful under the microscope,” the artist, relaying how the concept was birthed. “The images stayed in my mind. When I made two limited editions of ‘Virus’ in 2016, I didn’t know why. The images just came out while I was working in my studio at the Lorton Workhouse Arts Center.”

The center is one of the 16 buildings of the former Lorton Reformatory in Virginia that was refurbished in 2004 by the Lorton Arts Foundation as a visual and performing arts studio and exhibit area. For USD 4.2 million, Virginia’s Fairfax Country bought the 2,324 acres where the former prison was originally built in 2002 following its closure a year before. Opened to the public in 2008, the center retained the prison’s late 19th and early 20th century revival architecture designed by Snowden Ashford and Albert Harris.

“In 2016, I was specifically making an artwork based on the concept of combining two contrasting qualities, beauty and danger, in one piece. My other aim was to objectify, or magnify, what was invisible and secret to the eyes, through art. Those were my theoretical frameworks in the making of the ‘Virus,’” Mendoza says. He adds that the images intuitively twinkled in his eyes, and his hands naturally followed, from the kneading of the clay, to the shaping, glazing, and firing of the stoneware artwork.

After finishing his masters in Fine Arts at George Washington University, Mendoza went out to teach at such institutions at The Workhouse Arts Center, the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, and St. Thomas More Cathedral School. After a brief study at the Corcoran School, he came to Manila “to look for his roots while doing stoneware pottery.” The search continued with a meaningful mentorship under master ceramic artist Jon Lorenzo Pettyjohn in 1999. The two eventually put up the Pettyjohn-Mendoza School of Pottery in Makati, a landmark institution for serious Filipino potters that unfortunately closed in 2009.

While in Manila, Mendoza organized the first network of Southeast Asian potters after he received the Toyota Foundation's Network Program Grant in 2007. This led to a show featuring 38 Southeast Asian potters at the Ayala Museum in 2009. He became a resident-artist of Virginia’s Workhouse in March 2010, after he and his family left Manila and stayed in Virginia in late 2009.

No science in his mind

He could not remember if the virus he saw under the microscope was SARS, HiNi, Ebola, or Zika. There was no science in his mind nor readings that egged him to think of virus in art, ahead of COVID-19. “It just happened,” he says simply, while recalling the shivers that went down his spine in watching how his old artworks turned out like quaint and quiet glimpses of COVID’s menace.

Mendoza's predominantly brown District Clay Gallery "Virus" was displayed from November 19 to December 31, 2016.

“It’s like my past artworks are depicting a scary reality I am seeing now. How everyone is running away from COVID-19, how people around the world are running to safety, away from this destructive thing,” he shares.

The artist’s thought calls to mind the words of Filipino poet Virginia Moreno who, in describing the abstract sculptures of Napoleon Abueva, wrote in a 1960s poem, “nothing is real that is not first imaginary.”

In comparison, the reality of Mendoza’s abstract stoneware sculpture was first perceived under a microscope, its shape deeply secret and unknown to many. Giving life to that image is a leap of art, its beauty and its danger imagined first, before its real danger becoming part of life.

"In the Galleries: this art will really speak to you" Washinton Post, Arts and Style June 24, 2017 by Mark Jenkins

The Washinton Post, Arts and Style, June 24, 2017

by Mark Jenkins

Hadrian Mendoza

Ceramics are prone to breakage, so most potters avoid making pieces with protruding bits. But Hadrian Mendoza has apparently been in a prickly mood. The series that provides the title of his Zenith Salon show, “Dangerous Flower,” features toothy tendrils that bristle from spherical forms. These are inspired by the “mathematical design of the stamen,” a gallery note explains. But there also are a “Cactus,” a few large “Blooms” that resemble dinosaur mandibles and several busts of spiky-haired punk rockers.

Heads are as common as blossoms in this selection, in fact. The Philippines-bred local artist is showing a horizontal lineup of ceramic craniums that includes a cat-pig and an E.T. with large, goggle-like eyes. There also are a circular series in which glazes drip into moptops and a smaller set with elastic cords that dangle from skulls like dreadlocks. The forms are inventive, and so are the surfaces, which range from matte to glossy and uniform to mottled. The earthy colors emphasize that Mendoza’s work in made of clay, even when he transmutes it into something as a filmy as a flower or a cloud.

Dangerous Flower: Hadrian Mendoza On view through July 8 at Zenith Gallery, 1429 Iris St. NW. 202-783-2963. zenithgallery.com.

"Mysticism and post-colonial moorings in Hadrian Mendoza's stoneware" December 18, 2015 GMA News by Filipina Lippi

Virginia-based Fil-American stoneware potter Hadrian Mendoza has been creating artworks with many voices.

His solo exhibit, “A Round of Daydreams,” opened in Ayala Museum's ArtistSpace on December 5 and will next be shown in a private showroom of Galleria Duemila until next year.

The 65 artworks in the exhibit include post-colonial images of Bulol, the iconic wooden rice god of the north; wall-bound heads that display both ancient and post-modern visages essayed with a glocal sense; cubistic bamboos that balance and defy gravity (like Asian resiliency); and recent works titled “Tree of Life” and “Dancing (Blood) Moon” that dazzle with mysticism, their fire soaring beyond the limits of the functional art works that Mendoza is known for since he began honing his craft under the mentorship of master potter Jon Pettyjohn in the Philippines in 1997, and since he first touched clay while taking up art studies at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in 1996.

“What I learned in life and from doing art is that life is for living now. An imagination of what happens after life is a daydream,” he explains. To some observers, to soar is to daydream. And to balance, the original title of his exhibit at ArtistSpace, is a political act and also a necessary pause to understand mysticism and the unknown.

Tree of Life

Each of his six series of the 21 x 21 inch “Tree of Life” is a real vase that can hold water. “For me, their images float between the real life and the after-life,” says Mendoza, who began making the series a year and a half ago, when a vertical cylinder that he conjoined with a wheel-like shape on top of it reminded him of a tree.

“I made branches and fruits by punching random holes, added glass that gave a touch of floating bubbles, gay brightness, and the element of air on the [top] clay part of the tree. After firing, the heavy coat of porcelain slip on the clay’s surface looked like a storm or wind the tree has endured – it was a poetic piece,” he recalls.

Dancing Moon

Mendoza’s “Dancing Moon,” a set of 12" x 12" wall pieces, depicts a full moon’s dramatic transition into nothingness. The moon is made of green beer bottle fired into ox-blood stoneware splashed with brushstrokes of white porcelain slip. Like a pond of green haze, the glassy moon reflects the red color of its background.

“I began making my moon series in 2014, when I found out that glass melts, drips uncontrollably, and its color becomes brighter when fired into clay. The first time I made this series, the initial piece reminded me of the pulsating moon that I once saw when I was young and drinking with friends at the beach,” recalls Mendoza.

Dancing bamboo

His “Dancing Bamboo” series are perfect vases whose sections dart from left to right, then shoot upwards at sharp angles. “For me, they represent balance, evolution, growth, and reaching out. I made them by tilting the weight of several sections from one side to the other. Despite the stressful tilting, they turned out balanced and centered,” says Mendoza, adding, “I’ve been doing variations of the bamboo, but in early 2015, I was challenged to reconstruct the bamboo with a risky balancing act.”

Modern warriors

Mendoza’s “Warriors” are wall-bound heads. Minimal lines suggest eyes and lips. Rings and bones pierce sculpturally detailed noses. Colorful cords cascade from them like long hair. “I wanted to bring out the ancient and tribal warriors of the past. Some are hairy, others are bald, suggesting generations of people,” Mendoza explains.

“Different skin tones and hair colors suggest multi-races. They are united by the culture of nose piercing that young people in modern times have adopted. It is the effect of the Internet era, of well-travelled young people who respect and almost embrace all cultures. In this era of globalization, keeping one's culture is also a challenge. As a Fil-American who has rediscovered the Philippine culture but is back in the United Statesagain, I have to deal with different cultures and at the same time keep my own (cherished and chosen) cultural space. The Warriors is how human beings negotiate with globalization.”

Eternal Bulol

Mendoza’s Bulols have sculpted tattoos. They are tall, they look peaceful and they surprisingly stand strong and still on small bases.

Explaining how he has appropriated the Bulol as a source of what is authentic and original in a neo-colonial, neo-liberal, busy, dizzying, and negative world, Mendoza says, “I have become a tattoo artist to my Bulols, engraving carvings and not making mere lines on them – exactly the way I would have decorated my body if my skin was a blank canvas once again.” The mummies of ethnic groups in northern Luzon have tattoos, but the bulols in the same area are not at all embellished.

“I risked creating tall bulols on a small base, their knees jerking forward or backward, their hips carrying the weight of their bodies, not too far off from the base so they would not fall, lean, and tilt. And I gave them a peaceful look – to tell about mental and physical balance,” he adds.

Mendoza’s “Bulol in a Spin,” its head touching its feet, forming a circle with a 20-inch diameter, is the artist’s ultimate poetic license to morph his own bulol, making it his own authentic platform to essay what is good and evil, what is imagined and real in art.

His personal myths on love sealed in stoneware

Mendoza has started making art works about love and how different individuals negotiate in the name of love. “Fertility Gods and Goddesses” are two sculpted figures, their organs etched in the fold of their clothes, and they sway with orgasmic delight. “Third Eye” is a tall and slim figure with a red heart. It is part of a 40-inch piece with a head that looks like a mushroom or penis, while underneath is a face with minimal lines. Etched on the swaying body are V-shaped breasts and an inverted V for the organ.

“It is Mendoza’s best show yet,” assesses his mentor Pettyjohn.

Mendoza, who teaches at The Workhouse Arts Center in Lorton, Virginia, graduated with a degree in business management at the University of Mary Washington in 1996. He studied at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington and was part of the Pettyjohn-Mendoza School of Pottery in Makati City in 1999, a landmark institution for serious Filipino potters that unfortunately closed in 2009.

In Manila, he organized the first network of Southeast Asian potters after he received the Toyota Foundation's Network Program Grant in 2007. This led to a show featuring 38 Southeast Asian potters at the Ayala Museum in 2009.

Mendoza organized a second group show of ASEAN potters at FLICAM Museums in Fuping, China in 2012; and the third Southeast Asian Ceramics Festival and Exhibition at The Workhouse Arts Center in Lorton, Virginia in October 2014, after receiving the “Humanities Fellowship Grant” from the New York-based Asian Cultural Council. He became a resident-artist of Virginia’s Workhouse in March 2010. — BM, GMA News

- See more at: http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/548267/lifestyle/artandculture/mysticism-and-post-colonial-moorings-in-hadrian-mendoza-s-stoneware#sthash.U7mjuKH2.dpuf

"Shards and Shades" Metro Magazine March 2008 by Alya B. Honasan

It's supposed to be a barong-barong, but with shiny pottery shards stacked like a child's block against a sunny sky, the picture is far from glum. Instead, it's a celebration of different textures, colors and elements coming together as pottery meets paint, in the happy union of two media by young artist Camille Nieves "Kim" Dacanay-Mendoza.

"Its something that i've wanted to do ever since I started doing pottery some four years ago," says 28-year-old Kim. "I guess you call this a collage, because its an assemblage of different forms seeking new unity and new meaning."

The meaning naturally evolved from Kim's own state of being. Married to a talented potter Hadrian "Adee" Mendoza, she lives with him and their little daughter Banaue Marie in "paradise," at the foot of Mt. Makiling in Calamba, Laguna.

"Working in a pottery studio with my husband provided me with an abundant source of material" says Kim. "Pots are everywhere, and so are the shards and rejects that we mostly throw away. One day, I told myself, hey, maybe I can do something with the broken pieces, so I started putting the shards aside, collecting rejects from our firings and trimmings. I just do whatever the ceramic pieces tell me to do, and then accents the totality by painting the background," The ceramic pieces create an image in her head, Kim says, and the process is completed with a few strokes of oil paint.

Not that artistic pursuits are anything new; she was actually painting and sculpting first, having studied at the University of the Philippines College of Fine Arts, "where the system exposes students to different media before they can focus on their major." Then she enrolled in a pottery school run by Adee and Jon Pettyohn, and a new passion- as well as life partnership- was molded.

Kim believes that clay is the ultimate three dimensional medium, while with canvas, "depth is created through color and texture. When you put both materials to work, you created commonality: the painting achieves a three dimensional effect, while the ceramic pieces share in the illusion that the paint creates."

Part of the fun is figuring out just what the pieces of clay are trying to tell her. "Its all about discovering the significance of something that would appear utterly useless. I try to tweak them into saying something. I love it when I am able to give new life to something that's been otherwise discarded."

Talk about fruitful recycling: glazed triangle make lovely sails for boats on a blue sea while odd-shaped squares from the houses in "Squatter." Trimmings from the lip, the mouth of the pot in progress, makes perfect petals for flowers, curly strips of earth that literally pop off the canvass.

Kim recently concluded a successful show at Apartment 1B in Makati, and actually finds joy in balancing her art and her domestic duties as wife and young mother. "It's hard, but doable," she says with a laugh. "Well, i'm a full-time hands-on mom, but i've also been itching to work! When I did my show, I had to plan way, way ahead of the scheduled exhibit. for one thing, I could work only when Banaue was sleeping; awake, she demanded full attention. But then, there's a side to it that also contributed to my art. Banaue had been a source of both delight and discovery. She's growing up and looking at the world with fresh eyes, and oftentimes, I find myself rediscovering the world through her."

The rediscoveries will now reach a bigger audience, as Kim looks forward excitedly to her first show with Adee, to be held at the Philippine Center in New York this October. "He will fill the ground, and I will decorate the walls with my paintings. We've been preparing for this show for the past two years, and a good rhythm between our works has been established." A delightful rhythm indeed, whatever the medium.

"Form and Balance" Philippine Inquirer November 27, 2006 by Erlinda Bolido

Potter Hadrian Mendoza teams up with uncle Rachy Cuna for an exhibition of ceramic pieces and sculpture.

When Hadrian Mendoza had his first pottery exhibit about a decade ago, His uncle Rachy Cuna was perhaps the proudest of all, touting the show to his friends and acquaintances like a veteran impresario who knew he has a winner on his hands.

Mendoza was an accidental potter. He was home for an extended vacation, having lived in the United States for several years, when a serendipitous meeting with ceramic artist Jon Pettyhohn got him interested in pottery. After this show, he went back to the US for a while, then returned to become a "full-time" potter, making a name for himself and partnering with Pettyjohn in the Pettyhon-Mendoza workshop. Meanwhile his uncle, originally celebrated for his innovative and trend-setting floral arrangements, had also moved on, putting his talents to bear on such diverse projects as events and home-styling, painting, jewelry and home-accessory design.

Collaboration

It was not before uncle and nephew decided it was time for a family project, a joint show. Both Cuna and Mendoza agree it was the younger man who broached the idea of a collaborative exhibit. For Cuna, it was an opportunity to explore yet another field he had been wanting to go into- sculpture. "I had been doing sculpture but this is the first time I exhibit my work," he said. After a year of gestation the show "Reunion- balance and form" was born. It features 30 sculptures by Cuna and 60 pottery items by Mendoza. They divided the owrk by having Cuna take care of balance and Mendoza in charge of form.

Cuna's sculpted pieces are literally balancing acts- metal figures, many of them with human forms, holding crystal globes, feet firmly planted on solid kamagong blocks. The position of the feet changes ever so subtly, almost unnoticeable at first glance, from one image to the next.

"Dancing Hands of a Stoneware Potter" Philippine Panorama Magazine November 26, 2006 by Filippina Lippi

Stoneware potters have dancing hands. On their wheels, they slap a slab of clay, raise it to life, and push their creations beyond the limits of colors and forms only to aim for something beyond form.

Hadrian Mendoza, a stoneware potter for almost ten years has hands that can command the shapes of functional and sculptural forms, and eyes that are forever hungry for colors and their stunning effects. He has mastered the science of fire and chemicals. He has patiently learned about craftsmanship from mentors only to arrive at an understanding that there is something that he cannot control in his own field because pottery is also made by fire.

Nine years ago, while a student at the Corcoran School of Arts and Design in Washington, DC, Mendoza made a five-foot tall work entitled "Chain Vase." It was fired at his school's nine-foot tall kiln.

"Chain Vase" has strong horizontal lines traveling across its orange belly. Its six sections are deliberately shown, not hidden. "At the time, I didn't know how to hide the sections of a big jar. I could not make them look seamless. To break its form, i incorporated a long chain at a semi vertical angle across the tall jar," recalls Mendoza.

Interpreters say that the "Chain Vase" is raw and unconscious work of a Filipino artist who felt with intensity the clashes of culture, his and that of the host country, while he was growing up in the US.

Last year, Mendoza has embarked on a project to make another "Chain Vase." He was confident that he could recreate past works because of the expertise that he has acquired from his mentor, Jon Pettyjohn, who is known as the imminent father of Philippine pottery.

"But by way of working with clay has changed. The movement of my hands has changed," mendoza explains, adding, "My old Chain Vase has a stronger energy because I did it when I did not know so much about the discipline of pottery making."

Theoretically, repeating an old vase can be done by its creator. "To do that, I have to step back and try to change the position of my hands. I'll look at the pot, feel its lines and finger marks. I have to remember how i held my hands then. I'll work quickly with my palms instead of my fingers. I won't think much and I'll have fund doing my work," he says.

Mastery comes with technique. It is also the start of an arduous struggle to make beautiful pieces with energy that can delight more than bore with perfect craftsmanship.

"I have recreated my style as quick as I can for the past five years," says Mendoza, who is known among his peers for his penchant for expressionistic sculptural pieces and reinvented functional forms.

Recently, Mendoza has been experimenting dangerously. He has been stretching or "flopping" his clay for it to reach softness that might collapse when fired. "It is one way of creating works with grace and movement. Clay, as you know, is as hard as steel when fired," he says. He has allowed his glazes to run wild, for texture and stunning effect, even if uncontrolled drips can potentially ruin a pot during firing.

"It's like walking to the edge because all these things have to bed one quickly so that my stoneware pots are not ruined when they are fired," Mendoza explains.

He has been using two or three basic natural glazes" ipil ash which emit light greens; Pinatubo ash which radiate with browns and blues; and sugar cane ash which bring out shades of dark olive green.

"The point I am trying to reach by now is to make the glaze and the shape of my work as one," he says. Despite the array of his beautiful works, attaining this ideal "does not happen very often," he says.

A hard working potter controls the mixing and preparation of his clay, the shaping and the glazing of his works. "I do all these things," attests Mendoza.

Every potter knows that even if he has put everything in order, chemistry does its own magic such that the colors of stoneware pots burst or blend together on their own until they attain a kaleidoscope of vibrant colors. Funny, all these things happen while the pots are inside a shut kiln, with fire, and beyond man's touch.

"Natural Selection" High Life Magazine (Business World), November 2006 by Hans Audric Estialbo

Hans Audric Estialbo talks to two sculptors who are looking to tradition for a revolution.

It was curiosity that led me to The Pinto Art Gallery in Antipolo, the venue of the annual Antipolo Arts Festival. The annual convergence of painters, potters, sculptors and other artists picked an ideal setting: at the entrance to a city, yet still very much within the idyllic surroundings that characterize this small town just outside of Metro Manila. The religion ringing in the air was the art these people practice, most of them fresh talents in different media, and some of them familiar names, like Hadrian Mendoza. I first met Hadrian during a fund-raising exhibit to help stop women's prostitution in the Philippines. Hadrian was, by that time, already quite a prolific sculptor; he has always been a firm believer in sculpture's ability to connect a people to its origins. "Art is what keeps us connected with the roots we were born with. Amid technology and other modernity, pottery will survive the way it is surviving now," he said.

GLAZED LOOK

He has, in the past, been referred to as Philippine pottery's Picasso, having held an impressive number of exhibits in and out of the country and blown away a far more impressive number of enthusiasts with his skill in stoneware. In recent years, Hadrian has mounted shows that has left an unforgettable impression of what pottery, and Philippine pottery, for that matter, has to offer. His collection of functional pots, plates, bowls, tea sets, vases, glasses, pitchers, ans slabs, stood in Pinto Art Gallery for a far simpler context: reinvention. Potters like him, undeniably, are up for nothing less than reinvention.

Prior to this engagement, he had traveled and researched extensively to expand his craft. "The shades of greens and browns and red in my work come from ashes of ipil, pine, and fruit-bearing trees, most of which were destroyed by storms and strewn along Manila's South Super highway," he said. He has begged bakeshops for ashes, too; those who wood-fire their products were happy to supply him in return. He has visited sugar mills and riverbanks of silted cities outside Manila for sugarcane and volcanic ash, where he finds the orange and brown colors he seeks to use in his work.

Hadrian still relies on the traditional ways of making his masterpieces; where some go with the tide, he goes against the grain. It is the young potter's skill with glazing, however, that sets him apart. Glazes-both utilitarian and decorative- play a vital role to the potter, and Hadrian takes his glazes seriously., He has, in the past, shared his technique: blending three types of glaze and mixing them to create white streaks that adapt to any color. The combination of glazes has allowed him to achieve different results. His pieces are nothing short of inspired- be the chess sets, drinking glasses, basins, or a sculpture of the mythical half-horse, half-human tikbalang on a circular plinth of green clay.

Although Hadrian first trained in the US, it was not until he came home to the Philippines that his affinity for native themes became apparent. "Pottery is different here in the Philippines- which was why I came back home. It's just as different as those who practice it. It's like recreating nature in a more permanent way- taking things from the earth like clay, ashes, trees, sand, powder, altering them into your desired shape or form, glazing them with your creativity, firing a piece of clay that might just give you the brightest hue of the sky or the sea or even the universe. We, as Filipinos, keep it blooming. It's when you get down and dirty with dirt, ash, and clay that you feel the connection with the earth or with your culture," he said.

FIRE FROM WITHIN

It is this sense of connection to one's roots that is shared by another equally gifted potter, Pablo Capati III. Pablo is one of only tow people in the country who have mastered the anagama kiln, an ancient method first brought to Japan from Korea in the fifth century.

"Potters like us recreate the traditional- the natural- thing again. We create something to cope with the moderns. This is what keeps us rich," Pablo said. Pottery offers a raw connection, a spirited desire to just let the hands do the talking wile minutes and seconds disconnect one from a busy modern life. But like all things in the world, there is a diversification in pottery. The approaches that divide those who practice it are the same dynamics that keep them together. Pablo does this with anagama.

An anagama (meaning "cave kiln" in Japanese) consists of a firing chamber with a firebox at one end and a flue at the other. Anagama kilns are sometimes described as single-chamber kilns built in a sloping tunnel shape; in fact, ancient kilns were sometimes built by digging tunnels into banks of clay. Unlike electric- or gas-fueled kilns that contemporary potters use, the anagama is fueled by wood, where a large amount of fuel is needed for firing until an appropriate temperature is reached. Stoneware and porcelain pieces will typically mature at a measure of "heat work" dependent on the final temperature coupled with the time required to achieve that temperature, which would reach as high as 1,300 degrees celcius.

In this manner, fly ashes are produced as wood in the kiln is burned. Wood ash settles on the pieces during the firing, and in a complex interaction between ash, flame, and the minerals that make up the clay body, forms a natural ash glaze. The glaze shows incredible variation in all its texture, color, and thickness. It may range in texture from glossy and smooth, to rough and sharp.

Pablo said the placement of pieces within the kiln definitely affects the look of the piece; sometimes, the longer and the more fly ashes are present, the better and stronger the hues produced. As pieces closer to the firebox may receive eighty coats of ash, or even be immersed in embers, those deeper in the kiln may only be gently touched by ash effects.

Besides the location within the kiln, Pablo shared that the way pieces are placed near each other also affects the flame path an, naturally, the appearance of the pieces. The best thing about this, said Pablo, is that the potter can only imagine the flame path as it rushes trough the kilin and use this sense to paint the pieces with fire. This is why most of Pablo's works look raw, almost prehistoric. In contrast with Hadrian's, Pablos's creations come out with different hues, the effects significantly embossed in every stroke of color.

A slab in the middle of the gallery- the center piece of his collection- stood out from the rest of his works. This, he said, took a month to make, and was helped all along, by accident, by the quirks of the anagama. "It was supposedly a bigger slab that i tore in two, with my feet no less, and with the amazing faculties of wood firing, became what it is now." it was almost six feet high, ruined on the edges, with a surface that looked wounded and elegant at the same time.

The rest of his masterfully crafted pieces, created by the work of both hand and foot, took demanding hours to put together. Present in his gallery were big carved pots that swank of ash colors and splendid finish that are perfect for display. A big circular pot was in one corner, its powdery texture was the reason it stood out among the other objects around the area.

For both Hadrian and Pablo, nothing much has changed since potters of old expressed their art in clay and fire. In fact, they say, things should stay the same. Given the richness of Philippine culture, contemporary Filipino artists can look to their own selves for inspiration, and, through common methods of creating pottery, connect with a past they share with many other artists from distant parts.

"Hot Water" British Ceramic Review Magazine March/April 2006

Preview- The humble chawan and its noble roots are celebrated in a major international exhibition in Belgium. Ceramic Review takes a sip.

The connection between ceramics and tea-drinking has a rich, evolved culture. The qualities of handmade ceramic vessels have much in common with the virtues revered by the Japanese tea ceremony, or chanoyu, which developed into an art form after the ninth century when tea was introduced to Japan from China. Much like the ceramics it used, the simple act of tea drinking became symbolic in Japan of an appreciation of nature, simplicity and imperfection, an later a high art advocating harmony and balance.

The sweeping influence of this culture is celebrated in Joy of the Noble teacup, a major project organized in Belgium by Lou Smedts an Kaori Goyen-Chiba, to explore the ceramic heritage of the chawan, or the oriental tea bowl, and to trace its roots. Chawan makers from Asia, Europe and the Americas participating in the exhibition reveal a great diversity of vision relating to this simple vessel loaded with tradition. However simple, the chawan performs the essential role in the tea ceremony as the direct connection between hos and guest, and is therefore capable of transcending its humble function to assume a powerful cultural significance.

Among the sixty-seven participants from sixteen countries are Jack Doherty (UK), Roland Summer (Austria), Vladimir Shapovalov (Ukraine) and Akiko Ozutsumi (Japan). This evocative collection fascinates, tantalizes and resonates with the spirituality of the culture it celebrates.

Joy to the Noble Teacup is showing at Galleri La Fabrick, Hertsal, Belgium from March 12- April 2, and tours to Paris later in the spring. For further information, image gallery and future exhibition dates see: website www.jnt.info

Top: Chawans by Jon Lorenzo Pettyjohn and Hadrian Mendoza of the Philippines.

Bottom Left: Hilda Merom (Israel)

Bottom Right: Akiko Otzutsumi (Japan)

"For Your Table With Love" Metro Home Magazine Vol.3 #2 June 2006 by Alya Honasan

I wanted a wedding gift that was both a work of art and something that would become a part of the couple's everyday lives. I found it in a potter's studio...

Last year, my oldest nephew Kim announced that he and his long-time girlfriend, Nikki, were getting married. I adore my nephew, who's 10 years my junior and whom I practically watched grow up, and his wife-to-be is an equally intelligent and wonderful girl. So, when the two asked me to be a godmother- for the first time in my life!- at their Boracay wedding, after getting over the initial shock at the realization that I am indeed old enough to have kids of marrying age, I began my search for the perfect wedding gift.

I was, of course, pressured to find something both fabulous and unique with a corresponding hefty budget. I toyed with the idea of artwork, but somehow the idea of giving them something to hang on a wall or put on a table for static display did not appeal to me. The couple already has a full furnished house in Davao where Kim finished school and established his business, but they have also acquired a small tract of land of which to build a home in Boracay, where Nikki enjoys her work at the Mandala Spa. So, whatever I picked had to be appropriate for either an existing suburban home or a cozy beach house in the making.

And then, last January, I chanced upon a few pieces of stoneware pottery by Hadrian "Adee" Mendoza, the gifted young potter, one time protege of the great Jon Pettyjohn, and now a teacher and accomplished artist in his own right. I first encountered Adee's works up close when we featured him last year in the Sunday Inquirer Magazine, in conjunction with his two-man show with his mentor, and and i marveled at how his functional works had a modern edge, while remaining effortlessly utilitarian. His artworks, meanwhile, had the same edge, tempered with whimsy; his free-standing Tikbalang sculpture is a sleek tower, topped with a pensive little figure of mythological creature.

Adee discovered pottery through sheer serendipity, when the business graduate was looking for an elective course in his senior year of college at the Mary Washington College in Virginia. "It felt good in my hands," recalls the 32-year-old Adee. "And the possibilities were endless." After training in pottery studios in the US, he came home to Manila to apprentice with Pettyjohn, leading to a first one-man show in 1998 at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila, "7 Months in the Philippines." Since then, he has had about a dozen one-man shows and countless group exhibitions, the last being a solo show at the Philippine Center in New York last November, and is looking forward to a twin bill show with his uncle, stylist and designer Rachy Cuna, later this year.

Adee has moved back to Manila for good,m taking to heart the idea that pottery is very much intertwined with culture, and choosing to literally work with the soil he was born on. He married Kim Dacanay, also a pottery artist, last year, and they're expecting their first child in September.

Although Adee has set prices for his pieces, and charges less for big orders- a single, very large glazed platter would go for about P20,000, for example- I worked from the outer end, giving him a budget and asking him what he could do with it. His offer was a 34-piece table set for six- glasses, plates, saucers, bowls and coffee mugs- plus three serving platters and a pitcher.

Cognizant of the nature of handmade stoneware, and of the fact that artists work best when they've got a blue sky above them, I only told Adee that Kim and Nikki loved the sea, and he could use that as inspiration. Otherwise, it was entirely his call. As it turned out, giving Adee creative freedom was the best thing I could have done. "It's very important that a client trusts me," Adee says. "I always tell clients to give allowance for change and surprises. If somebody comes to me with very detailed specifications, I usually say no."

About a month after we spoke, Adee fired a test plate and told me on the phone how "beach" it looked. He originally planned on white plates, but he also asked if I had any objections to using colors like blue and brown, as some apparently didn't like eating off colored plates. "My pamangkins will eat off anything," I told him. "Please go wild."

The results, completed after two months, and as you can see on these pages were exquisite. Adee played around with the idea of sand, water and a soft shoreline, and the plates and saucers depicted a beach and endless blue horizon. The mugs, the large vases and pitcher carried the colors of sand and sea at night, while the bowls called to min drops of water left on the sand after the waves have receded. The masterpieces, to my mind was the stunning platter with different glazes that Adee had poured on while he turned the edges. It looks like what you would see when you drop a rock in the shallows- a patch of bare sand in the center, with the water radiating in different shades and consistencies around it. It took all my willpower not to keep the platter for myself!

All in all, I was very pleased with the results. As of this writing, Kim and Nikki have yet to see the set, but I'm certain they'll love it. And I'm tickled at the thought that two people I love very dearly will be eating off works of art, everyday of their lives.

"Art Pottery" Mirror Magazine May-June 2006 by Lita C. Lee

Coming home from a scholarship at the Institute of Classical Architecture in New York, Kim Dacanay-Mendoza found herself flying airplanes before discovering her passion for pottery.

While searching for her place in the sun, Camille "Kim" Dacanay-Mendoza found her passion for pottery.

"I was listless coming home from a summer scholarship at the Institute of classical architecture in New York City," says Kim, who graduated from the University of the Philippines Colelage of Fine Arts major in sculpture.

"I wasn't quite sure of what to do, what work I could pursue. I enrolled at a flying school. Flying airplanes was easy; the difficult part was in landing the plane. My parents were scared and I was getting stressed."

On the prodding of her mom, Kim checked out a pottery school in Makati run by the well known potter from Los Banos, Laguna, Jon Pettyjohn. "At day one I was hooked, probably because I missed handling clay, which was what I did in college. I went to the Pettyjohn-Mendoza pottery school twice a week but wanted to attend more classes, so I asked Tessy Pettyjohn if they have other classes.

She said "Go to Adee Mendoza's class." What I did not know was that I was being set up with Adee, who had studied business in Mary Washington College in Virginia but decided to come home and be a full-time potter here.

"We became friends instantly. I apprenticed with him. I didn't want to stop doing pottery and told myself this is what i want to do."

Not long afterwards, Adee and Kim became partners, not only in pottery making. They got married in 2005.

They live in a comfortable house surrounded by nature with a workshop close by at the foothills of Mt. Makiling in Calamba, Laguna. Two rottweilers keep them company.

As a potter, you make functional pieces of artwork, says Kim. "It is an intimate kind of art, because you tend to use your pieces everyday. The difference between pottery and sculpture is that, with sculpture you work longer to finish a piece. I use modeling clay in sculpture and its feel is quite different from the clay used in pottery.

"Masarap gamitin ang clay. With potter's clay, though, you have to work continuously until the clay allotment is used up. Otherwise tumitigas ito. It's not like sculpture, where you can pause and then pick up again where you left off."

After doing pottery for tow and a half years, Kim is still at it as though she just picked it up yesterday. "This is the craft for me, I hope, for life. I will stay with pottery because i like it. This is what I want to do. I can always go back to sculpture if I want to."

Adee and Kim had a sold-out show last November in New York, at the Philippine Center. This month, Kim will have a show at Beyond Bamboo in Makati City, with an assortment of vases, plates and fan pots, among others. Another show is planned for December.

To be a good potter, says Kim, "you need to have discipline, as in everything else. And lots of patience, too."

She says she makes an average of about 20 pottery pieces a day. "I work every day, as much as possible. Most of the pieces are sold in shows. A few are orders for clients. We have clients like Armida Seiguion-Reyna and some foreigners. Last year we did just fine in spite of the sluggish economy."

For the moment, she says she is taking it easy because she is expecting their first baby in September. "This is more important than anything else," she says. "But I still try to put in some work in the morning, and from 2-5 in the afternoon."

"it is quite fulfilling to see all the work you've done. The studio feels sad if it's empty. Adee and I get the urge to fill it up."

Kim says she gets a lot of ideas from reading. "I ready a lot, an influence from my parents (journalists Barbara and Alex Dacanay).

"Sometimes, designs and ideas come in my dreams. And I try to draw or put them on paper. I have a doodle book for that. Then i discuss it with Adee to see if an idea works or not."

"He is my mentor. I ask him anything. We inspire each other but when we are working in the studio, we don't disturb each other. We each do our own thing."

Kim and Adee are among the few artists in the country who are dedicated to pottery. They are the junior colleagues of the Pettyjohn couple, Jon and Tessy. Adee is Jon's partner in the pottery school.

"Our works are similar in the sense that w create functional art pieces," says Kim. "But we are not the only ones in the craft. There are some upcoming ones, and we gather once a year for the pottery tiangge at Glorietta in Makati. We have organized a foundation called Putik."

"Doing pottery is a very rewarding endeavor, kahit physically masakit ito sa katawan," says Kim, "Especially after the pieces are fired, and you see the various ways that the designs have come out."

There is always excitement when we open the kiln. each piece is truly one of a kind. Each batch always has a surprise. There are times when I feel I don't wnat to part with certain pieces or batches. I get selfishly attached sometimes.

"But then, unlike with sculpture, in pottery you make a lot and it is easier to let go. I definitely don't want to let go of my sculptures. I have not let go with many of my sculptures kasi I do it with passion. With pottery you are a bit like a machine: You make and make. Pottery also requires passion, but since you produce several pieces by the lot, it's easier to let go."

"Selling art pottery is hard if you don't know anyone. Hard, because it is expensive. But then, engaging in this craft is a joyous endeavor, because you are doing what you want to do. Masaya magtrabaho, even if you work alone."

"Every single piece of pottery I do is creative. Pottery changed my life- completely. My parents are happier because I am doing what I like. I resisted doing art at first but eventually I found my art for me. Now I am no longer lost, I am found. In time, I will be good in this craft. I will keep trying to do better than the last time. And my name, hopefully, will be associated with pottery as well."

"High on Pots" Filipinas Magazine April 2006 by Barbara Mae Dacanay

Filipino American sculptor and potter Hadrian Mendoza draws on Filipino indigenous culture for inspiration for his creations.

For the past nine years, Hadrian Mendoza, a Philippine-born artist from Washington DC has been making intermittent trips to his homeland in arduous search for indigenous color and form for his pots.

The search for identity, common among Filipino artists and writers who are based in the Philippines, is unusual for Mendoza who grew up and studied in the United States.

"I have been coming home for culture," Mendoza says of his sojourn in Manila in 1997, after finishing a business Administration coursed at Mary Washington College in Virginia, and a year of studies at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington DC.

"Bulol" is the latest of his search for the heart and soul of Philippine pottery.

Bulol is the wooden rice god of the Igorots who made the world-renowned rice terraces in Banaue, northern Philippines two tousand years ago. The antique rice god had an over sized bald head, oval shaped eyes, protruding ears with holes, a wasp waist, short and small limbs with hands on knees. Mendoza's stoneware version is a shining and colorful bulol with open knees, seated on top of a big circle with a vertical pedestal.

Mendoza's other recent experimentation in the Philippine shape is "Tikbalang;" a powerful half-horse / half-man figure in Philippine folklore. His "Tikbalang" has a powerful organ that is half-hidden under long legs. It's also seated atop a giant ring on a pedestal.

According to folk legend in the Philippines, the tikbalang's knees are higher than its head. The creature lives in dense forests and slimy swamps, and waylays travelers who can find their way again by wearing shirts in reverse.

In 2004, Mendoza created a colorful series of "Manunggul," a boatman carrying a passenger into the other world. Mendoza has propped the eerie-looking boatman and his passenger on top of a colorful ring and a vertical base, as if to overpower the pull of the death boat.

He was inspired by the Manunggul jar, a 3,000-year-old funeral vessel (dated 710 and 890 BC) which was unearthed by Filipino and American archaeologists in the Tabon Caves of Palawan in southwestern Philippines in 1964. It was discovered with a 22,000-year-old skull, which is now known as the Tabon man. The elaborately designed Manunggul jar has been described as the most beautiful vase unearthed in Southeast Asia. The Philippine government has declared it a national treasure. It is now illustrated on the 1,000 peso bill.

"The emotion I feel when working in the same spirit of these ancient works is a powerful one," he says of his creative process, adding, "I ask myself how and why these pots are Filipino. I still run around in circles. As I contemplate what I will do next, I feel something boiling inside of me."

"Looking at books and pictures of ancient Filipino forms and sculptures, I have incorporated into my work a version of my own," he explains. Why not? "There are many versions of Filipino idols and gods, all have morphed in the hands of their creators, each new one evolving into artworks of modern era."

In past shows in Manila, Mendoza's bamboo forms signified his seriousness about cultural identity. The hankering for something Filipino has always been with him even while he was a student in the US. In 1996 he made "Bahay Kubo," a creative rendition of a Philippine nipa hut in stoneware.

Before venturing into sculptural works and conscious search for Philippine forms, Mendoza disciplined himself with functional pieces in the tradition of Asia's master craftsmen.

His pots, plates, tea sets, bowls, pitchers, glasses, slab plates, and vases are a craftsman's happy re-invention of the functional pieces often used and taken for granted at home.

Mendoza had also become a shaman in conjuring unusual colors on his pots. "Juicy" hues run a swirl blazing on round and flat surfaces. Colors simmer or flare, making his pieces as brilliant and luminous as Manila's sunset, or as lush as the Philippine countryside. They imbue his pottery with emotions; temperamental or shy, bold or conservative, all hinting of a Filipino soul.

Mendoza had patiently searched for the magic of "natural" colors in Manila and in the provinces.

He gets Storm-struck pine trees along Manila's South Super Highways. Their ashes give various shades of green. He scouts for ipil and fruit-bearing trees in the forest of Laguna in Southern Luzon, for variants of blues, browns and reds. He begs for ashes from bakers with wood-fired ovens. He retrieves sacks of sugarcane ash from sugar mills. He scrounges for the ashes of Mount Pinatubo (which erupted in 1991) from silted riverbanks in Angeles City, 45 kilometers north of Manila. It has twin colors, light brown and orange.

"Now, I know how to get a nice blue-white swirl in the middle of a plate," he boasts of his enormous plates that shine with memories of Philippine landscape.

The use of natural glaze has become an art movement among Philippine potters. "Parts of trees and sand are made into powder and ash. Using them as glaze on a piece of clay, who knows, after firing, their colors might give a hint of the sky, nature or the universe. Its like recreating nature in a more permanent way," Mendoza explains.

Which aspect of pottery is more challenging, the shape or the color? "Now that I can make any shape, I think glazing will be the challenge for the rest of my life" he answers.

Mendoza was a recipient of the prestigious Anne and Arnold Abramson award for excellence in ceramics in 1996. But an eight-month apprenticeship in 1997 in Manila with Jon Pettyjohn, a half American- half Filipino artist acknowledged as the father of Philippine pottery, mad Mendoza decide on a life long commitment to pottery. Together, they set up the Pettyjohn-Mendoza Pottery School in Makati in November 1999.

Mendoza built his studio with a gas fired kiln in Makiling, Laguna in February 2001. Since 2004, he has been teaching at the Makiling high school for the arts, also in Laguna. Participating in pottery festivals in Japan and South Korea from 2002-2005 has brought him to the heart of Asia's way about pots.

"Hadrian Mendoza at the Philippine Center" Newstar Philippines Vol. 40 December 2005 by Robert P. DeTagle

Hadrian Mendoza will exhibit 50 pieces for his ceramic exhibit at the Philippine Center from November 7 to 18, highlighted by his exploration of various glazes and by inclusion of his Bulol series sculpture.

Mendoza has worked in or traveled to the Philippines since 1997, after college in Virginia and studies at the Corcoran School of Arts in Washington DC, where he was awarded the Anne and Arnold Abramson award for Excellence in Ceramics. The 30-year-old is particularly excited about this show.

He told this writer, "I have prepared about eight months for this and the works have changed a lot in that time frame. My ceramic works use all Philippine-based materials of clay and ash."

The ashes can be from ipil or pine trees or sugarcane or from Mount Pinatubo, even from the wood burned in bakeries in the Philippines.

"I made some glazes from pine trees that were destroyed by storms and strewn along Manila's South Super Highway," he recalls, yielding "light green- not celadon- but different shades of green."

The result is a collection of brilliant ceramics that incorporate his image of forms indigenous to the Philippines. His glazes will lead to unique pieces: "I have used combinations of glazes over and over again, and the results are always different."

He has also included two works from a series, called "Bulol," based on the Igorot rice god.

"There are many versions of Filipino idols and gods, and all have morphed in the hands of their creators, each new one evolving into artworks of a modern era," Mendoza says.

Mendoza decided to continue the path of pottery after apprenticing with Jon Pettyjohn. They founded the Pettyjohn-Mendoza Pottery School in Manila in lat 1999. He teaches at the Makiling School of Arts in Laguna. With his frequent forays to other Asian countries, he has sought to further research and explore indigenous forms that he seeks to re-imagine in his striking works.

"Master's Apprentice" The Philippine Enquirer November 7, 2004 by Joy Rojas

It was meant to fill up a light semester, this pottery course that Hadrian Mendoza took during his last year in college in 1995. So imagine everyone's surprise when he, a US-based business major who set his sight on becoming a chef, junked all his grand plans to pursue a passion he didn't know he had.

"I was hooked. I liked working with the material from day one," says Mendoza, whose only two experiences with pottery then were molding colorful Playdoh as a child and living in a home teeming with his mother's antique jar collection. "Although my works weren't really good at the time and I knew that being a potter was going to be hard, my professor told me, "Stick with it because you're going to be good at it someday."

Nine years later, Mendoza finds himself in the middle of his most important show to date- a back-to-back exhibition with Jon Pettyjohn at the Art Space in Glorietta 4, Ayala Center, Makati. It is a match-up both daunting and inevitable, with his modern stoneware platters and vases displayed to Pettyjohn's traditional pots and jars. Mendoza, who taught pottery in camps and community centers in Virginia, served as an apprentice for eight months in 1997 to Pettyjohn, whose name and the word "pottery" are practically interchangeable in the local art scene. For Mendoza, sharing the spotlight with a man "who set the bar on how a potter should be, has challenged me to push myself further and put out my best works yet."

He's certainly got the technique down pat; making his own clay, one of many thing he learned from Pettyjohn, is now deemed "second nature." For now, the struggle, he admits, lies in "trying to figure out what a Filipino pot is like, so when someone sees your work, he knows instantly that it comes from this region. I don't know if I'm successful at that."

Mendoza was halfway around the world when he arrived at an epiphany. Back in the States after apprenticing with Pettyjohn, "It suddenly dawned upon me," says Mendoza, " how I've always been taught that ceramics reflects the way people lived at a certain age and time- why they made their pots, burial jars and idols the way they did. Knowing that pottery and culture are intertwined, I realized then that I would be lying to myself as an artist if I worked with clay in a place where I wasn't born. That's the reason I came back. To find my culture."

Mendoza, in fact, would find more than his culture upon his return; he found a home, setting up a school with Pettyjohn in Greenbelt, Makati in November 1999, and a studio with a gas fire kiln in Makiling, Laguna, where he resides. Today, the young potter teaches twice weekly in Makati and on Sundays since October, at the prestigious Makiling School of the Arts. "I still have a lot to learn," says Mendoza who also offered the pottery course in UP. "But I know enough to teach kids to open their minds about the possibility that pottery may be the art for them. Don't leave your options to just painting, sculpture, metal or wood. Give this a chance and see what clay can do for you."

Tattoos streaming from his arms up to his fingers suggest a tough, rebel streak. But Mendoza, nephew of famed Floral Architect of the Philippines Rachy Cuna, is actually a gentle soul who leans towards wholesome, outdoor activities. He plays basketball and badminton, walks his two Rottweilers, and likes to go on long drives whenever he needs breathing space from work. He also likes to listen to Pinoy rock (Bamboo and Kapatid are on his playlist) and used to hang around a lot with bands. But those days are over since "it kind of messes up my schedule at work."

Shrugs Mendoza, who speaks with an American twang: "Ganoon, eh, that's all i do. I don't drink and i don't go to bars. My life revolves around pottery. It sounds sad," he observes with a laugh, "but actually it's not."

The element of surprise is what piques this potter's interest; the irony that no matter how much control you exercise over the clay, the final results are almost always, literally out of your hands. Surveying his stoneware pieces, the would-be chef who walked into a pottery class nine years ago says, "Nothing here has been set in stone in my mind before it was made. Zero. In pottery, you have to respect the fire and the way the clay behaves. You also have to be very patient and forgiving of your medium. Of course, you're always hoping that things work out the way you want it. But when it doesn't, you just have to accept it as neither bad nor good."

Reflects Mendoza: "That's the high that you never lose. Whenever I feel drained from work, I open up my kiln and I'm reminded of why I am here."

"Calling the pot art" The Philippine Star Magazine November 7, 2004 by Raymz Maribojoc

What makes an artist?

Jon Lorenzo Pettyjohn, 54, who has been working with pottery for more than thirty years, readily admits that he doesn't know. "Who's to say?" he asks. "Would a painter who isn't very good be more of an artist then, say a very good pottery or any other craftsman?" Here Jon touches on the old argument of art versus craft. "A lot of people still have this idea that art is painting, or sculpture, that art isn't functional (as opposed to decorative). There's this sort of elitist thinkin going on, but slowly, we're starting to change that."

In a country where pottery has been emerging as a "legitimate" art since only a few decades ago, he is among a growing number of potters working to increases the awareness of clay as a medium, of the potter's wheel being capable of self-expression as much as canvas or marble.

As co-founder of the Pettyjohn-Mendoza Pottery School and president of Putik (Association of Philippine Potters, Inc.), Jon has been part of the movement for the recognition of ceramics in the Philippines as art since he has moved here in 1978.

In 1972, he studied in Escuela Masana, a school for the arts in Madrid, and apprenticed for two years in pursuit of his craft. When he visited the Philippines in 1976, he decided the country would be a good place to settle. He also met and married Tessie San Juan, who was also working in clay.

In the beginning, though, interest began to mount. After a few exhibitions, people began to drive to their studio in Pansol, Laguna, asking Jon and Tessie to teach them. Jon was at first reluctant to do so, wanting to prioritize his own work. "I didn't really want to teach. Then there were these people really driving out, sometimes all the way from Manila, and i'd teach a few. Eventually they started taking over the studio," he remembers laughing.

As a result, in 1994 he opened up a school in the Madrigal Art Center, where he met promising young potter Hadrian Mendoza. "He wanted to learn all about it, and he'd come up to me with questions, and he was very god at what he did, even back then. Eventually he asked to work with me as an apprentice, and then he moved to the states after a few years." When the school moved to Makati in 1998, Jon invited Hadrian back to the country to help him with teaching, and founded the Pettyjohn-Mendoza Pottery School.

By that time Hadrian and Jon were participation overseas in international pottery festivals, and were being exposed to other ceramic cultures. They realized that more had to be done to put the Philippines on the pottery map. By 2003, they and a few more pottery artists and enthusiasts formed Putik, the first organization of its kind in the country, to promote their art and serve as a unified body for the exchange of ideas, resources, and support. With dozens of members, not just artists but people from all fields, Putik has proven to be a success, so far.

"Now, we're so organized," remarks Tessie. "Before the foundation, it would take forever to get anything done- exhibits, demonstrations. Now we work so fast!" With more than thirty members, and more coming in, Putik is now poised to announce its presence to the country: from now until December, they will be holding the First Philippine Pottery Festival in Greenbelt, a two-month long celebration with exhibits, pottery demonstrations and classes to encourage more people to get into ceramics.

They're also starting to make their way into schools. They now hold classes at the Philippine High School for the Arts in Mount Makiling, Los Banos, and are working with the UP College of Fine Arts to develop a curriculum for pottery.

All this, and all of these years are leading o the promotion of Philippine pottery. "Eventually, we (Putik) want to be recognized internationally. We'd like to participate in festivals, to ask foreign potters to come here and share their ideas, to be able to help the local artists."

With big plans for the future of pottery in the Philippines, they're also content with enjoying what they do. "it's great," says Jon. "I get to wake up every morning and look forward to doing what I like to do. We're all still having a good time."

"I used to consider myself as an artist, when I was young, but now I'm not so sure. I think art is really all about perfection, whether it's in paint, or clay, or whatever. Actually, I don't consider myself a good pottery... That's why I keep going at it, trying to attain that level of perfection."

Now, with Putik, the school and an increasing number of students, pottery is on its way to receiving wider recognition in the country. Jon, Tessie and Hadrian have their hands full molding their students as they mold with clay on a wheel.

"Hit the pot" Real Living magazine June 2004 by Apol Lejano

A piece of pottery with a wide crack in two places used to serve rice on my dining table. It was a real conversation piece, and not because diners would grind their teeth on broken-off bits of bowl. The imperfections were all part of the design. After potter Hadrian Mendoza had shaped the item into a medium-sized half sphere with smooth sides, he had made the slits, before finishing off with a glaze of gray and white.

Maybe it was tempting fate, for the dinner party came that a clumsy guest decided that the cracks were not enough, and the rice bowl ended up in the trash. So when last February Hadrian exhibited pieces at Mag:net Gallery in Makati, with two other potters in the show called "Centering," off I went to have a look.

No cracks, breaks, and stabs this time, as had been this particular potter's style in previous years. Now the pieces are more controlled and fluid, more traditional, actually. Ask Hadrian and he will tell you that this is him taking his craft more seriously. No more room for error now; a miscalculation cannot be remedied by a touch of deconstruction. You'll be informed that it has to do with turning 30, which he did a few months back. "Now is the time to start going for your goals," he says, "to push yourself past your limits."

We have to watch this guy , then, if in the coming years he intends to go for it more then he has in the past. It's been 10 years since he took a short course on pottery and gotten hooked on it. So despite the business degree earned from Mary Washington College in Virginia, U.S., Hadrian decided not to enter the corporate world, but rather get jobs at pottery studios to learn more of the craft. "My main goal was to work, work, work." So manic he was that he even exhausted teachers at the Corcoran School of Arts, where for a year and a half he was a part-time student. "They told me that it was time to move on," he says. "I was putting a big dent on supplies, using a lot of clay all over the place. I was always in the studio and my pots where everywhere."

Local pottery Jon Pettyjohn was not turned off when, in 1997, Hadrian came to the Philippines for a year to work as his apprentice. In 1999, with Hadrian back in the States, he got a call from Pettyjohn, asking if he was interested in working together. Shortly after, the Pettyjohn-Mendoza School of Pottery was born.

For the past years now, in their space in Greenbelt, Makati, students have been learning to work with clay. It is only when you handle he material yourself do you realize that making a bowl is not an easy thing. First comes wedging, where with your two hands performing twisting and breaking-off motions you handle a ball of clay, aiming to get an even consistency. Then comes centering, a tricky process that requires your hands to position the clay exactly right, aligning the particles of earth just so, while a foot turns madly to get the kick wheel going. You push into the middle of the lump of clay now, opening and making smooth what will be the bottom of the bowl. Your foot still moves. After this, raise the clay to form sides, shaping as you go along.

When you're satisfied with the form, the work is still not done.. There is the trimming of the base, the application of glaze, and the firing. All the steps require hours of practice to perfect. You need reach only the middle part, sighing with relief that the sides of your bowl did not separate clear off its base, to realize that this is a serious craft. A potter cannot be lazy.

Hadrian has ideas playing in his head, some new, others taking off from stuff he's done in the past. "Never let yourself be satisfied with what you do," he proclaims. "There's always a quick satisfaction in something- a new color, a new form- but you shouldn't dwell on it too long," Advice well taken; time to stop thinking about cracked rice bowls then.

"The Picasso of Philippine Pottery" Gulf News June 4, 2004 by Barbara Mae Dacanay

Mendoza has perfected the abstract and minimalist forms that went well in the making of stoneware pottery

Hadrian Mendoza, 30, a stoneware maker, can be called the Picasso of Philippine pottery because of his fearless and audacious search for the unusual and indigenous forms, including expressionistic shapes, despite the limitations of pots and vases.

Mendoza was a business administration graduate of the Mary Washington College and a one year old student at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington D.C., before he hankered for roots and willfully transported himself to Manila to become a stoneware potter by end of 1997.

"I gave myself 10 years to pottery then," he recalled.

At the start, he had an eight-month of apprenticeship with Jon Pettyjohn, a famous Fil-American master potter in the Philippines. Mendoza's quid pro quo for the master then was "energy for wisdom in pot making". True, Mendoza was on the road to become a humble craftsman.

"But the truth is, I wanted to put some culture into my work. I didn't know how, but I knew it could be done by working in my own country," Mendoza explained.

While in Manila, he meditated on being a Filipino. In the process, he slowly metamorphosed into an individualistic and a nationalistic artist with a keen and hungry eye for Southeast Asia's indigenous forms, even as he perfected the abstract and minimalist forms that went well in the making of stoneware pottery, the way it is currently done in the Philippines.

The perfection of his craft, he said, always remained inversely proportional to his intense and deliberate attempts at achieving heavy cultural undertones for his works, a predicament that began when he vowed to be become a potter while he was still in the US.

In eight years, Mendoza has made three distinct phases that could be called major landmarks in Philippine pottery, in terms of achieving meaning and symbols for his works.

From 1996 to 1997, while he was still an arts student in the US, he made 30 gigantic jars, some of them taller than his 1.77 metres.

His "Chain Vase," made in early 1997, is a tall brown jar with a distorted, semi-sunken, and anguished mouth. Its tapering body and round belly are textured with coils that were earlier shaped by his fingers. The vase is decorated with criss-crossing black chain that, after a long glance, begins to look like a spine.

Gaping windows

Another piece, entitled, "Bahay Kubo (the Philippines' nipa hut)," has four round pots stacked on top of the other. There are small gaping windows (or wounds) at the seams where they are connected, making them stand tall with fragility. The whole piece is embossed with spine-looking chain.

"The bahay-kubo was implanted in my mind (when I was a young boy). But when I was making pottery, I didn't realise that I was making bahay-kubo with pots until the whole piece was fired," he said.

Mendoza's first jars have become archetypal of his "coming of age," of a voice that strongly speaks of rejection of oppression, of a strong desire for manhood, identity, dignity, and the flowering of one's culture, a passion common nowadays among many Asian artists who have been separated, by force, from their own cultural milieu.

"I think I have found my home here," he said. It was a subtle way of saying, "I don't want to be alienated again," a phrase often heard from many talented Fil-Americans, who in search of intensities and identity, have decided to come home and arduously embrace their own culture, with intuition more than reason.